To evade racist immigration laws, most Korean migrants entering the U.S. in the early 20th century kept up a long-term identity as students.

In a study published this fall in Ethnic and Racial Studies, sociology professor Sunmin Kim traces the stories of several of these migrants as they moved from the U.S. education system and workforce and wrangled with immigration officials. Their individual stories highlight the difficulties faced by Korean migrants, and how these challenges were impacted by social class and gender.

"Virtually every Korean migrant told immigration officials that they were going to attend a college in the U.S.," says Kim, a senior author of the study. "We think this dynamic is the reason why the Korean American community, or Asian American community as a whole, came to respect the figure of students in their community."

Kim co-authored the study with Carolyn Choi, who held a postdoctoral fellowship in Asian American studies at Dartmouth and is now an assistant professor of American Studies at Princeton University.

The 1917 Immigration Act prevented Asian migrants from entering the U.S. unless they could prove that they were merchants, diplomats, or students. The policy was founded in racial prejudice, says Kim.

"White policy makers and the public alike thought all Asian culture was 'too different' from American culture and regarded Asians as fundamentally unfit for life in the United States," he says. "Thus they implemented race-based wholesale exclusion with a few exceptions, because diplomatic and trade ties with Asia were still valuable."

While most Chinese migrants entered the U.S. as merchants during this period, Korean migrants were more likely to enter the country as students—in part due to the influence of missionary schools in Korea. But after 1924, it was illegal for former international students to remain in the U.S. after finishing their education, which meant that Korean student migrants had to deal with continual surveillance.

To uncover the lives of these early Korean migrants, the researchers leveraged 331 digitized files from the National Archives at San Francisco that span from the early 1910s to the 1940s. Kim and Choi were aided by undergraduate research assistants Joseph Chong '22 and Amy Park '23, who sorted through and summarized the files.

"Joseph and Amy did a great job of carefully reading through all the files and discovering the stories that spoke to them," says Kim. "By chance, all of the people involved in this project are of Korean descent, so it became very much a community project. We got a great kick out of it, and it also made all of us feel more attached to the Korean community."

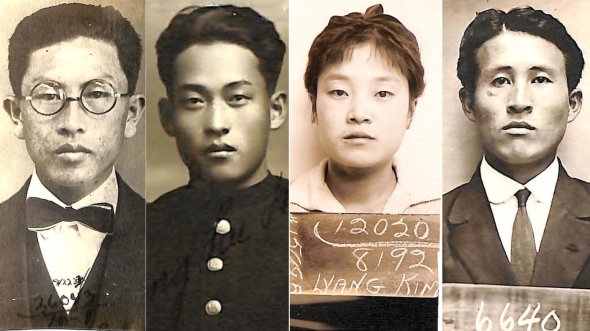

Po Han Pyung, Hahn Hong, Ryang Kim, and Tyung Soon Oh as pictured on their U.S. immigration paperwork (National Archives at San Francisco)

To evade racist immigration laws, most Korean migrants entering the U.S. in the early 20th century kept up a long-term identity as students.

In a study published this fall in Ethnic and Racial Studies, sociology professor Sunmin Kim traces the stories of several of these migrants as they moved from the U.S. education system and workforce and wrangled with immigration officials. Their individual stories highlight the difficulties faced by Korean migrants, and how these challenges were impacted by social class and gender.

"Virtually every Korean migrant told immigration officials that they were going to attend a college in the U.S.," says Kim, a senior author of the study. "We think this dynamic is the reason why the Korean American community, or Asian American community as a whole, came to respect the figure of students in their community."

Kim co-authored the study with Carolyn Choi, who held a postdoctoral fellowship in Asian American studies at Dartmouth and is now an assistant professor of American Studies at Princeton University.

The 1917 Immigration Act prevented Asian migrants from entering the U.S. unless they could prove that they were merchants, diplomats, or students. The policy was founded in racial prejudice, says Kim.

"White policy makers and the public alike thought all Asian culture was 'too different' from American culture and regarded Asians as fundamentally unfit for life in the United States," he says. "Thus they implemented race-based wholesale exclusion with a few exceptions, because diplomatic and trade ties with Asia were still valuable."

While most Chinese migrants entered the U.S. as merchants during this period, Korean migrants were more likely to enter the country as students—in part due to the influence of missionary schools in Korea. But after 1924, it was illegal for former international students to remain in the U.S. after finishing their education, which meant that Korean student migrants had to deal with continual surveillance.

To uncover the lives of these early Korean migrants, the researchers leveraged 331 digitized files from the National Archives at San Francisco that span from the early 1910s to the 1940s. Kim and Choi were aided by undergraduate research assistants Joseph Chong '22 and Amy Park '23, who sorted through and summarized the files.

"Joseph and Amy did a great job of carefully reading through all the files and discovering the stories that spoke to them," says Kim. "By chance, all of the people involved in this project are of Korean descent, so it became very much a community project. We got a great kick out of it, and it also made all of us feel more attached to the Korean community."