Each year, a dedicated group of undergraduate students take on one of the most ambitious challenges of their academic careers: the senior honors thesis.

Working closely with a faculty advisor, students develop and pursue an original research or creative project that goes far beyond the classroom.

Daphne Muhammad ’25, for example, worked with professor Kiara Sanchez to design and conduct an ambitious field study examining how conversations about race shape relationships among racially diverse groups.

In addition to presenting their projects to faculty and peers in their respective departments and programs, many students share their work externally—such as Will Ermarth ’25 and Maya Magee ’25, who led poster sessions about their innovative work in quantitative social science with professor Herbert Chang at this year’s Midwest Political Science Association Conference.

For many students, the impact of their senior theses are felt for years to come. Take, for instance, Emily Gao ’24, who built an algorithm as part of her senior thesis that ultimately enhanced Dartmouth’s course selection process.

This year, more than 300 students completed senior honors theses. From exploring animal metaphors in classic Greek literature to investigating the impact of invasive leaf litter on Bermudian micro-snails, to authoring an original poetry collection, students across Arts and Sciences disciplines blended curiosity, creativity, and deep research to make original contributions to their fields.

“I believe that you will never forget the excellent work you have done here,” Dean Elizabeth F. Smith said at a celebratory dinner this month honoring students and faculty who worked together on senior theses. “In fact, many of you will build your career around it. For others, it will be an influential stepping stone for lifelong learning.”

Professor Sonu Bedi and Jared Pugh ’25

Rethinking cruelty and the Eighth Amendment

In high school, Jared Pugh ’25 witnessed a young Black man being sentenced to 35 years in prison for first-degree murder. It was a moment that profoundly changed him—and inspired his quest to understand what it means to be imprisoned in contemporary times.

Pugh’s thesis examines the Eighth Amendment, which protects the incarcerated from cruel and unusual punishment, and the Supreme Court’s interpretation regarding prison conditions.

“Jared’s thesis nicely combines constitutional law and political theory,” says government professor Sonu Bedi, Pugh’s faculty advisor. “He argues for a novel interpretation of the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, focusing on the conditions of the punishment rather than the punishment itself.”

Pugh, a double major in government and African and African American studies, calls for a shift from the current “deliberate indifference” standard to a positive right to humane conditions, realized through a legal standard of strict liability. “The current legal framework requires incarcerated plaintiffs to prove that prison officials intentionally disregarded harm, making it difficult to hold the state accountable due to this arduous burden,” he explains.

Throughout the year, Pugh conducted extensive legal, historical, and theoretical research on the Eighth Amendment, prison conditions, rehabilitation as a theory of punishment, and racialization. He reviewed notable Supreme Court cases to examine how courts have interpreted cruel and unusual punishment, and researched some of the most despicable conditions that prisoners have endured.

“Initially, I believed legal protections doctrinally ensured a baseline of humane prison conditions, but my research revealed how the ‘deliberate indifference’ standard makes it nearly impossible for incarcerated individuals to seek justice and remedy violations against them,” Pugh says.

While the project has taken an emotional toll on Pugh, it has also driven him to pursue a career in prison reform. After graduation, Pugh plans to work as a litigation paralegal at Paul, Weiss for a year before applying to joint JD/PhD programs.

“This thesis has pushed me to critically analyze the intersection of law, race, and punishment, reinforcing my commitment to legal reform and deepening my understanding of the suffering of those pushed to the margins of society,” he says.

Professor Siddhartha Jayanti and Karun Ram ’25

Algorithms that power our digital world

Karun Ram ’25, a double major in math and computer science, finds beauty in the “simple” and “elegant” solutions of complex algorithms.

For his thesis, Ram is working to prove that the Jayanti-Tarjan Union-Find algorithm is linearizable, or that all its operations happen one after another, even though they may be executed concurrently, or simultaneously. When an algorithm is linearizable, it ensures consistent results and reliable use of an algorithm.

“Concurrency as a paradigm for algorithms is fascinating—it challenges our intuitions for what makes algorithms correct and makes us think about algorithms as almost strategic problems rather than procedural,” says Ram.

In this case, the algorithm Ram is researching helps to cluster large data sets and analyze large graphs and networks. For instance, it can search for groups of connected people on social media platforms with billions of users.

“As computers are becoming more and more critical to our everyday lives, ensuring that code that we run on them is correct and bug-free through formal verification is ever-more important,” says computer science professor Siddhartha Jayanti, Ram’s faculty advisor. “Verifying algorithms for modern multiprocessors can be particularly challenging. As part of the Distributed Computing and Verification Lab, Karun has been working on understanding and verifying such tricky multiprocessor algorithms.”

As part of his thesis, Ram is writing a three-part, machine-certified verification for the algorithm. Written in the formal specification language TLA+, the verification includes a “spec” (a description of exactly how the algorithm is supposed to behave), an “invariant” (a statement that is always true, regardless of the way the algorithm behaves), and a proof that shows the invariant remains true the whole time the algorithm runs.

The level of detail and precision involved in this research has been a welcome surprise to Ram, who will work as a quantitative researcher after graduation. “Working with both concurrent algorithms and machine-verifiable proofs requires a lot of precision—one misplaced symbol can completely invalidate an argument,” he says.

“In my prior experience with algorithms and theoretical computer science, intuition has been centrally important and sometimes precision and adequate formalism get left behind. This project has challenged the way I think.”

Lily Easter ’25 directing a rehearsal of The Wolves

From the stage to the director’s chair

Lily Easter ’25 isn’t part of Dartmouth’s women’s club soccer team, but after shadowing a practice and carpooling back to campus with them, she felt like she was.

This fieldwork was research for Easter’s honors thesis project: directing a production of Sarah DeLappe’s The Wolves, a play that follows an all-girls high school soccer team as they navigate big questions and wage tiny battles, highlighting the breadth and nuance of what it’s like to be a teenage girl.

“The senior thesis in theater gives students the time, resources, and mentoring necessary to create a major project in their area of concentration,” says theater professor Peter Hackett, one of Easter’s faculty advisors. “Lily put together a wonderful ensemble of actors and designers for The Wolves. The result was an entertaining, witty, and insightful look into the lives of a group of young women facing life’s most difficult challenges for the first time.”

In choosing the play, Easter considered the message she wanted to leave behind. “Reflecting on my past four years here, I thought about how my feelings and thoughts about womanhood have changed since coming to Dartmouth,” says Easter, who is majoring in theater modified with English. “In high school, my gender was not something I felt particularly strongly about or even thought about often. In college, however, the thought of what it means to be a woman was ever-present.”

To bring the production to life, she directed 10 student actors, four student designers, two student stage managers, and worked closely with many faculty and staff in the Department of Theater.

The project took her in new directions, learning the ropes as she went. Easter recalls the first day of blocking—establishing when and where actors move throughout the play—and the feeling of having everyone’s eyes on her looking for direction. It didn’t take long for her to settle in and build a great working relationship with all those involved.

“I have primarily worked as an actor in the past, so expanding the work to include designers and external elements was a new challenge for me,” says Easter, who plans to pursue a master of fine arts in acting or directing. “Through this project, I have learned so much more about different aspects of theater—lights, sound, scenic design, costumes—that I hadn’t had much experience in before.”

(Watch Easter talk about her thesis experience at @dartmouthartsci on Instagram.)

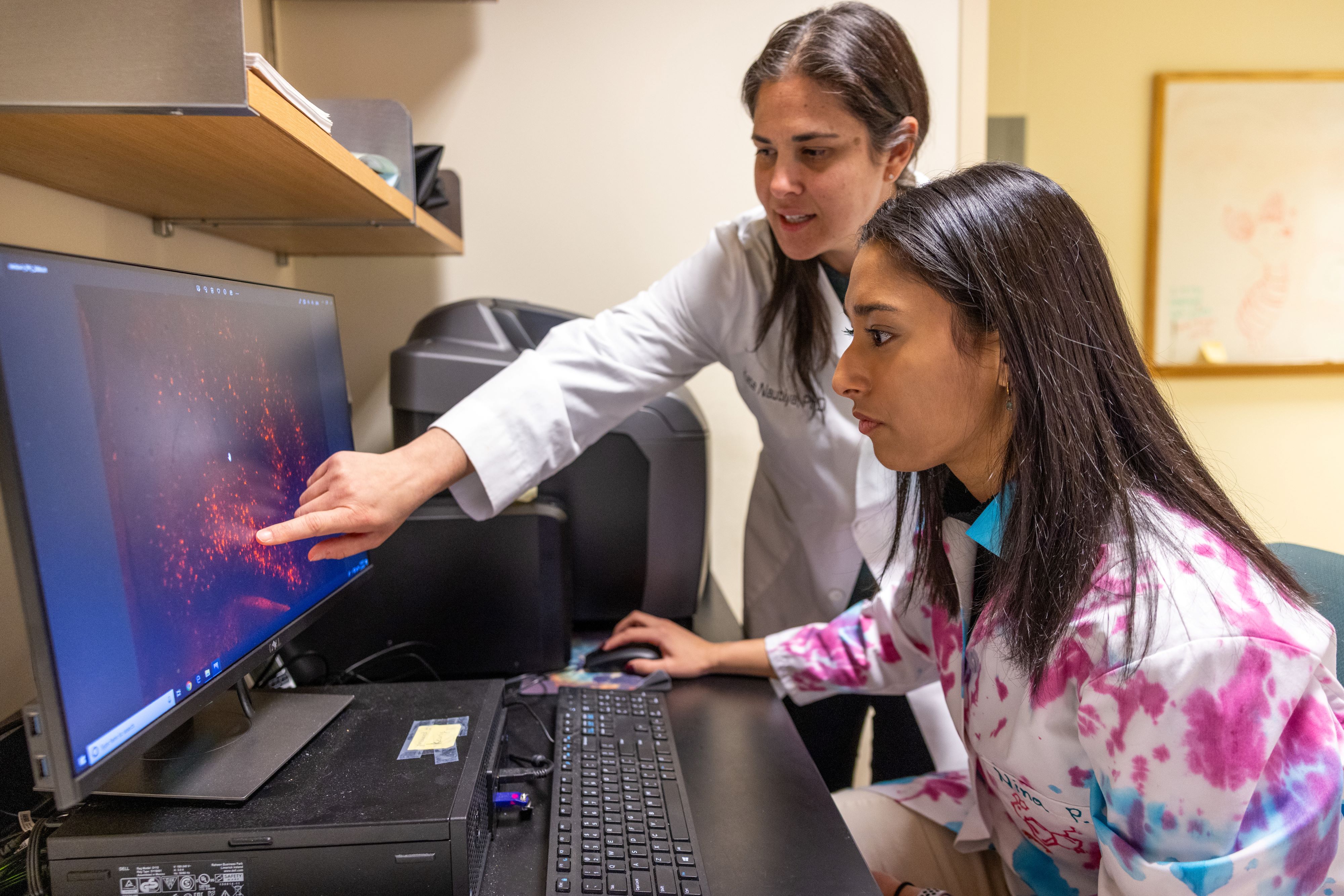

Professor Katherine Nautiyal and Nina Prakash ’25

Reimagining depression treatment

Nina Prakash ’25 wants to improve treatment of major depressive disorder and the impact it has on quality of life. “Current treatments are costly and slow acting, require a strict regimen, and fail to provide relief for a significant portion of patients,” she explains.

A neuroscience major on the pre-med track, Prakash is researching the antidepressant potential of psilocybin, the hallucinogenic component in magic mushrooms. She is looking into the brain’s neuroplasticity, or its ability to form and reorganize synaptic connections, when psilocybin’s active metabolite, which resembles serotonin, binds with the serotonin 1B receptor.

“The neuroscience senior thesis program has enabled Nina to explore cutting-edge research on the use of psychedelic treatments in psychiatry,” says psychological and brain sciences professor Katherine Nautiyal, Prakash’s faculty advisor. “Her project is tackling the critical question of how psilocybin can change the brain to support the clinical benefits seen in the treatment of depression. Her studies are on the forefront of this rapidly growing field, and it has been a pleasure to watch Nina carve out her unique contribution.”

Prakash used mouse models to conduct her research in Nautiyal’s lab. She examined images of the brains of mice that were injected with psilocybin and the brains of mice injected with saline, the control group, to analyze the psilocybin’s effects on neuroplasticity. “I’ve been blown away by the cool technology we have,” she says, “like the fluorescent microscope and behavioral testing setups!”

Prakash, who is applying to medical school, believes that psilocybin is a fast-acting, long-lasting alternative to existing treatments that could provide substantial relief for those struggling with depression.

“This project has really piqued my interest in the intersection of biology, neuroscience, and mental health,” she says. “I find it fascinating and rewarding to think that this research has the potential to contribute to a therapeutic that could really help people who are suffering.”