Most plants form beneficial relationships with belowground mycorrhizal fungi that help them access soil nutrients in exchange for sugars. These plant-fungal relationships are the most common type of symbiosis in the world, but scientists know very little about the ways that fungal species’ characteristics relate to their distribution, function, and resilience.

In a new study published in Scientific Data, Dartmouth researchers present a comprehensive database that catalogues the spore traits of 344 mycorrhizal fungi species. By consolidating existing but neglected knowledge of mycorrhizal traits, the database will help scientists study how fungi—and the plants they support—respond to stressors such as climate change and land use.

“Mycorrhizal fungi are everywhere, yet we still know much less about their traits compared to plants and animals,” says lead author Bala Chaudhary, an associate professor of environmental studies. “It’s our hope that researchers will use this database to interrogate new questions about the evolutionary history and functional diversity of this ecologically and economically important group of fungi.”

The researchers focused on the most common type of mycorrhizal fungi, arbuscular mycorrhizal (or AM) fungi, which form relationships with a wide variety of plants, including grasses, shrubs, trees, and most agricultural crops. AM fungi live their whole lives belowground, forming large networks of rootlike webs called mycelium.

Eventually, Chaudhary would like to catalogue mycelium traits, but the team started by examining fungal spores: the microscopic, thick-walled clumps of cells that fungi use to reproduce and spread.

“Taxonomists have been recording the inherent morphological variation in spore traits for many, many years, but this information has not been used to make ecological and evolutionary inferences,” says Chaudhary. “This was an effort to boost trait data for mycorrhizal fungi and make it easier to access so that it can be used by an open science community.”

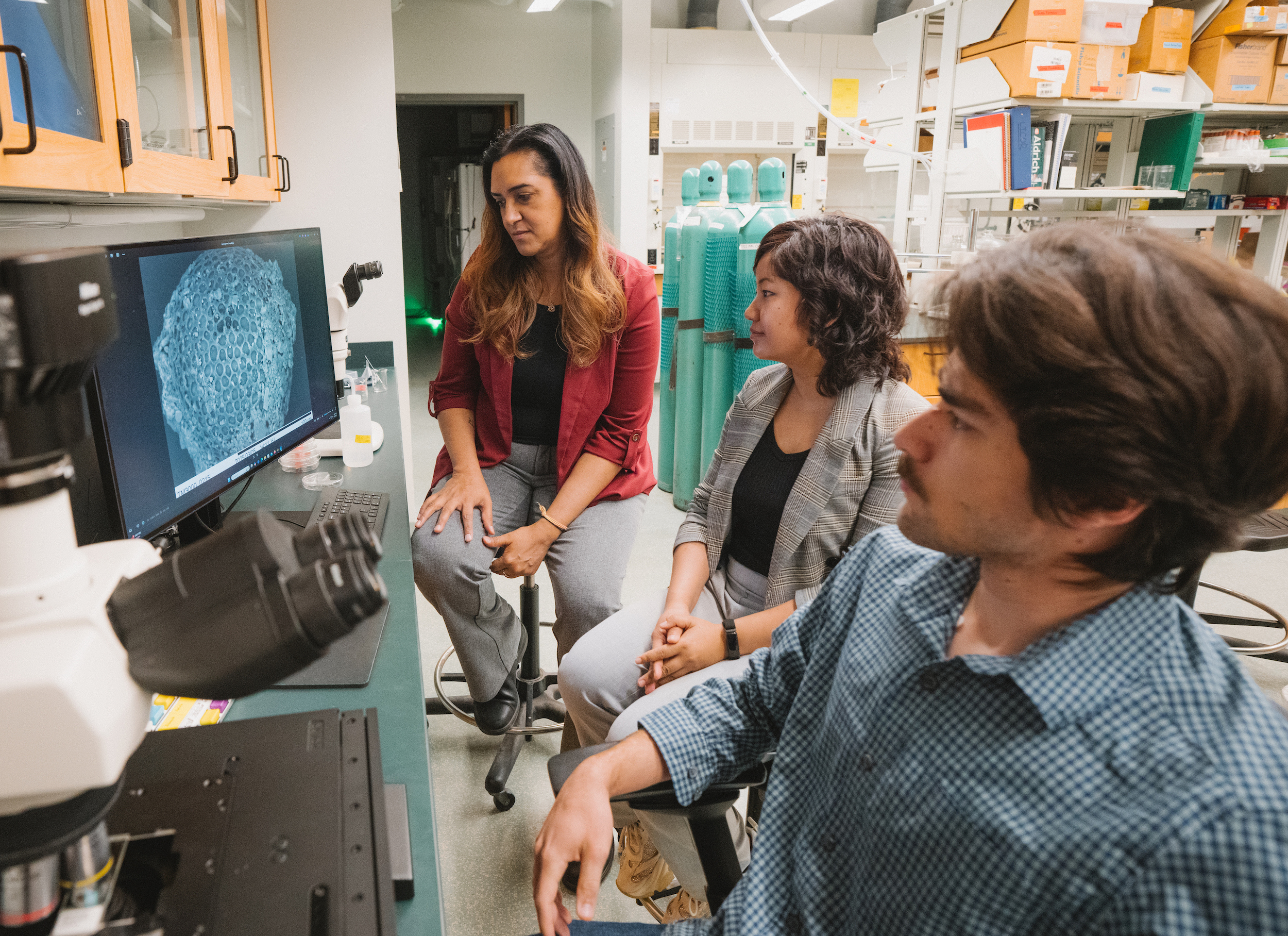

Bala Chaudhary, Smriti Pehim Limbu, and Liam Nokes ’25

Chaudhary spearheaded the project in 2019, but building the spore database was a massive, years-long collaborative effort.

“This project would not have come to fruition without our amazing lab,” says Chaudhary. “A lot of students and lab members have worked on this project over the years—from undergraduates to postdocs to other faculty collaborators. Our research community is just so special; it's what I love the most about being a professor at Dartmouth.”

The team spent several years searching through the scientific literature for fungal species descriptions. For each species, they collected information about the spores’ size, shape, surface ornamentation (e.g., presence of spikes, bumps), color, and wall thickness.

“We were digging up papers in different languages and getting all this really valuable data from sources that were collecting dust—some of these species descriptions were more than 100 years old,” says co-author Liam Nokes ’25, who began working on the project during his freshman year.

“These taxonomists never would have thought that their science would be used in this way, but that's the cool thing about basic science: you just don't know what information or knowledge it will generate in the future,” says Chaudhary.

Now that the database is compiled, the team is eager to put it to use. They already have several studies underway, including an investigation of the pros and cons of producing large or small spores, and a study looking at how spore traits relate to global fungal species distribution and resilience.

“We found that fungi that produce larger spores are able to thrive in warmer and wetter climates, but they cannot be dispersed as far, so there is a trade-off,” says Smriti Pehim Limbu, co-author on the new study and a postdoctoral fellow in Chaudhary’s lab.

“There has been a huge amount of interest and excitement in the research community,” says Chaudhary. “We shared some of the results last year at the International Conference on Mycorrhiza and there was a buzz around the data; people were tweeting about it, and I've gotten emails from colleagues saying that they are excited to use the data. It’s been really gratifying to have interest and excitement around this open data product.”