After wrapping up work on her 2024 book Mortevivum: Photography and the Politics of the Visual, which examines how documentary photography links Blackness with suffering and death, Kimberly Juanita Brown found herself continuing to grapple with the book’s disturbing themes.

“Mortevivum was difficult for me to write,” says Brown, an associate professor of English and creative writing and the inaugural director of Dartmouth’s Institute for Black Intellectual and Cultural Life. “It involved graphic images, cultural disregard. I needed something that brought together my research concerns while allowing me space to write about the beauty of Black cultural productions.”

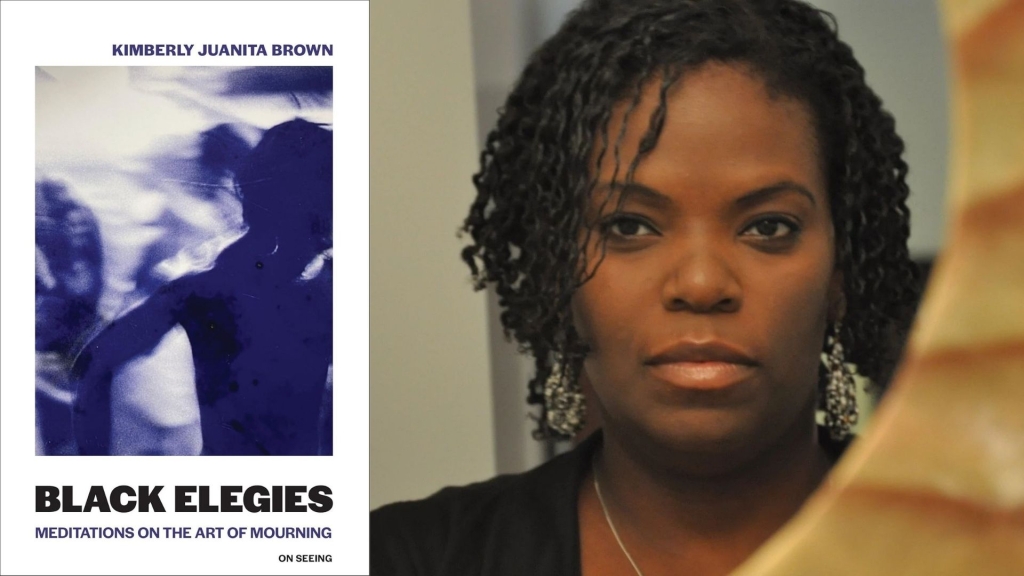

She describes her new book, Black Elegies: Meditations on the Art of Mourning, as part of her “recovery from the toll of writing about Black death.”

Mortevivum and Black Elegies are the first two titles of On Seeing, a new MIT Press publication series devoted to visual literacy. Each title will be published as a print book, ebook, and open access digital edition created by Brown University Digital Publications.

Black Elegies examines the ways in which Black grief finds expression across art forms—from fiction and music to film and poetry. Brown investigates both recognizable sites of mourning, such as forced migration and enslavement, as well as those less traditionally associated with grief: a spontaneous street party, quilt, dance performance, or musical instrument.

“I wanted to show that Black mourning practices are multi-genre productions and are not limited to one form or artistic output,” she says.

Brown selected some works based on her teaching, such as Toni Morrison’s Jazz and the photography of Roy DeCarava; others from museum exhibitions, such as Steve McQueen’s Ashes and Jeannette Ehlers’ short video Black Bullets; and poetry, fiction, and films from a range of artists and writers “all dealing in one way or another with grief.”

Across mediums, Brown makes the case that Black grief can be found everywhere: “It spills out of photographs and modulates music,” she writes. “It hovers in the tenor and tone of cinematic performances. It resides in the body like an inspired concept, waiting for its articulation.”

One example she points to is Ehlers’ Black Bullets (2012), which was inspired by the Haitian Revolution of 1791. Filmed on location at La Citadelle in Haiti, the piece “commemorates the unknown men, women, and children who participated in the Haitian Revolution,” Brown says. “It is elegant and somber, looping, and rhythmic. It’s a gorgeous piece of art.”

Ultimately, Brown hopes that her book “assists in the illumination of the way art and mourning are often co-mingled, particularly when antiblackness insists upon forced improvisation and evasion.”

“About Black subjects, Thomas Jefferson wrote, ‘Their griefs are transient,’” Brown says. “No, they are not.”