Luis Alvarez León’s research spans economics, geography, media studies, politics, and technology.

An associate professor in the Department of Geography, he says that his expansive scholarship traces back to the humanities.

As an undergraduate English major in Mexico, Alvarez León was often drawn to the cultural and geographical context around the literature he was reading. “I was doing a lot of translation from English into Spanish and vice versa, and I became interested in why certain cities have become hubs for book publishing, and how translation played a role in this,” he says.

To learn more, he signed up for a course on comparative urbanism run by the University of California in Mexico City. “That’s where it clicked for me that what I was really interested in was how places become what they are in terms of their economic dynamism, their cultural spheres, and the products that emerge from them.”

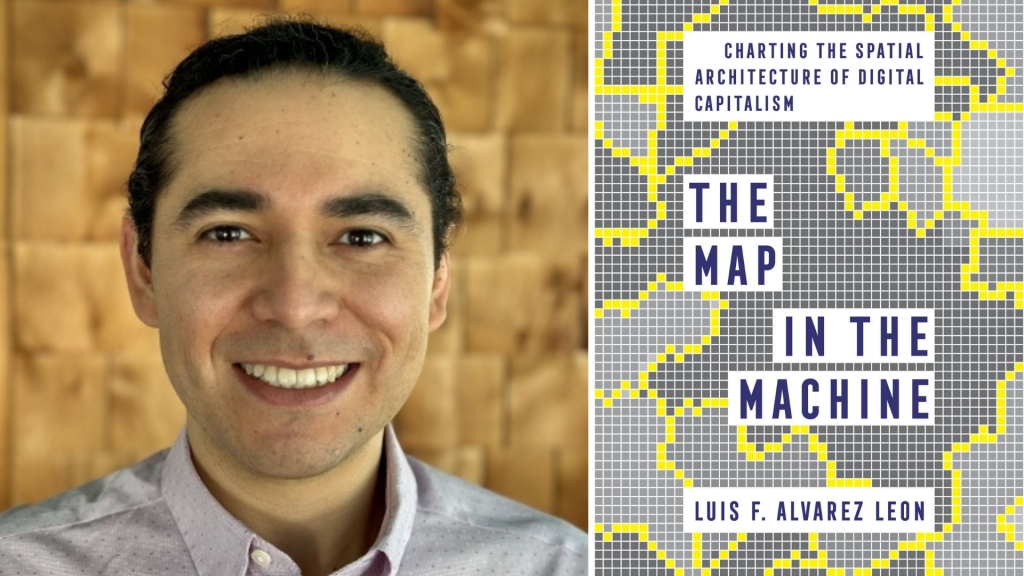

Alvarez León’s first book, The Map in the Machine: Charting the Spatial Architecture of Digital Capitalism, examines how location technology and data create markets for digital goods and services—and ultimately, shape communities and ways of life.

In a Q&A, he discusses the impetus for the book, his framework for understanding digital capitalism, and current research.

How did the idea for your book, The Map in the Machine, come to you?

For my master’s thesis, I examined how Netflix and other streaming platforms like Hulu and Apple TV were coming into the film and television industry and essentially disrupting an economy that was deeply rooted in Los Angeles. They were challenging the balance of power and, more importantly, changing the geography of not only how and where movies are made, but also where they are marketed and their global circulation. That’s when I became obsessed with the interaction between the digital and more material aspects of where things are produced.

A key enabler of the streaming markets worldwide was the fact that content could be tailored depending on where you access it. When I returned to Mexico to visit family, I would have access to a completely different catalog of Netflix titles. At first it didn’t make sense because it’s the same account, and I’m the same user. I went down a rabbit hole trying to figure out exactly how this happens. I began to think in more specific terms about the role of location, and geography more generally, in creating digital markets. That’s how the idea underlying the book emerged.

For many decades, it was a widely advertised notion that information was untethered from geography, that it could travel instantaneously and what you accessed on the Internet had nothing to do with the material place you were in. The book tries to dismantle this myth that the internet, information, and the digital economy are placeless. It then asks: What role does geography play in shaping digital markets, digital information flows, and the construction of this system that I call digital capitalism?

You offer a three-pronged framework to understand how these digital markets launch and function. That framework hinges on location, valuation, and marketization: First, the resources are located geographically, then their value is determined, and finally digital markets are created around them. Can you unpack this theory a bit?

It is the very ability to locate data on the internet that gives information value and creates markets. The fact that you can locate where a person is, through their GPS coordinates on their phone, means you can then give them advertisements that respond to their particular trajectories, update your offerings in terms of the deals that they can access, or even change the map—when they're navigating on Google Maps or Apple Maps, for example—to reflect different landmarks depending on who the users are.

And if you connect their location with, say, their purchasing history, behavioral data, social media data, etc., you can create markets that depend on where you want people to access or not be able to access those goods.

In the book, I offer a wide range of examples to show that the interplay of location, valuation, and marketization is not specific to any one industry, but really pervades everything from mobility and transportation to scientific endeavors to advertising, to how we access mundane things like food.

You also underscore that the relationship between geographical location and the digital economy isn’t static; rather, each side constantly adapts to the other. Can you offer an example?

Think about the transformation of bookstores in the past 30 years or so. If you remember You’ve Got Mail, the movie from the 1990s, it was all about how a small, family-owned bookstore was put under threat of extinction by a big, bad Barnes & Noble–like store. Then in the 2000s and 2010s, Barnes & Noble became the little bookstore under threat when Amazon came to town. And that has been the case for the past 15 years or so. We’ve seen a decimation of stores, large and small.

But I wouldn’t say this is predetermined. During the pandemic, Barnes & Noble was one of the companies that saw a huge surge in their interest valuation. Then they were reopening stores. The CEO of Barnes & Noble decided to give a lot more leeway to the people who were running the individual stores to tailor them to the interests of the local community. So we are seeing a lot of “placemaking” in response. Businesses attract people not only by their offerings of products and competitive prices; they provide places for interaction, for perhaps even community building through live events.

There’s a back and forth between the digital and the physical. And our landscapes are reconstructed in a way that reflects that triangulation among the digital and physical and our preferences, behaviors, and social interactions.

In the book, you probe the complex technical, regulatory, and governance issues surrounding digital capitalism. What are some examples of the questions that arise?

How are these transactions taxed? Who is assigned a responsibility for them? Who can you call if something goes wrong, or if there's identity theft or fraud, or if you have a complaint? Does it depend on where the user is located, where the company is headquartered, or where the servers are located?

If you're just buying something from the grocery store, but you're doing it through Instacart, it's mediated through a digital platform. That actually changes the type of transaction, how it's governed, the privacy rules around it, how the money is allocated, and the balance of power—now the transaction is not just between you and the grocery store, there's an intermediary there that may be accruing a lot of power.

On that note, you suggest that we, as a society, should take proactive steps in moderating and shaping these digital economies.

I think problems emerge when we have not intervened in the concentration of power behind the digital ecosystems dictating how people live their lives and how communities exist.

What are the political structures we can leverage to either guide in a gentle way, or reign in in a more forceful way, how digital ecosystems develop? Maybe that is through regulation, breaking up monopolies, antitrust laws, or privacy legislation to prevent the collection of certain data or alert users how their data are being used.

I’m very interested in the initiatives the European Union has developed to protect users and consumers in terms of the data that are collected and their digital rights. This connects with how they are thinking about building a single digital market for the entire European Union. What is the balance of power among corporations, everyday people, and the state?

You’re currently working on a book with urban planner and professor Jovanna Rosen about digitization and urbanization. How are you examining this complex relationship?

We have been developing this concept called the digital growth machine to try to understand the coalition of actors that call the shots in cities as digital industries and tools become more central. It is based on a theory from the 1970s called the growth machine, which looked at the different coalitions of influential movers and shakers in city politics, specifically when it came to the use of land. So you can think of real estate developers as a key actor, as well as municipal governments.

To update that idea, we’re bringing in digital as a factor to take seriously in urban politics. What happens when your transit services get outsourced to Google, Uber, or self-driving Waymo robotaxis, for example? What happens when the influential industry in your city is not, for instance, aerospace or film, but rather Google, Salesforce, Facebook, and X? What kind of tax breaks or policies or deals do they get, and how do they mold the city around their particular needs and priorities? We’re looking at how the interactions between urban and digital forces reshape cities.