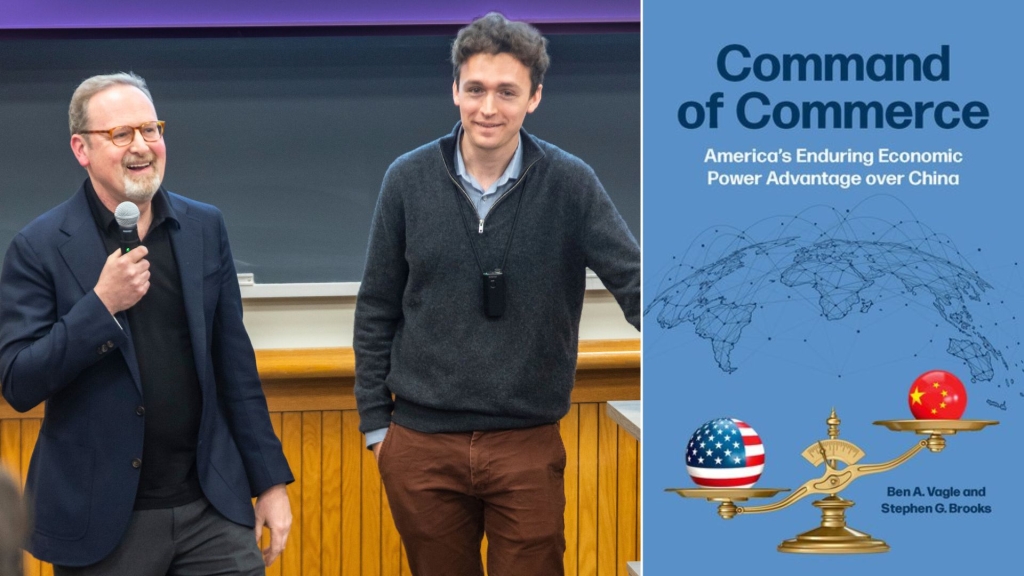

As a senior at Dartmouth, Ben Vagle ’22 set out to complete a thesis—never expecting that it would grow three years later into a co-authored book with his faculty advisor, government professor Stephen Brooks.

Newly published from Oxford University Press, Command of Commerce: America’s Enduring Economic Power Advantage Over China argues that contrary to common belief, China still lags behind America in economic power—and would suffer significantly more from a broad economic cutoff during a conflict than would the United States.

“The book overturns two pillars of conventional wisdom,” explains Vagle, who spoke with Brooks about the book at a talk on campus in April. “The first is that China is a peer, or nearly a peer, of the United States economically. The second is that the United States would incur economic losses as great as, or greater than, those of China during a conflict over Taiwan if the U.S. were to initiate a broad economic cutoff of Beijing.”

Watch the book talk with Professor Stephen Brooks and Ben Vagle '22 on campus in April 2025.

In a Q&A, Vagle and Brooks discuss their findings, the relevance of the book, and their policy suggestions for Washington to maintain America’s political and economic advantage. (This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.)

What gave you the conviction to work together to turn the thesis into a book?

Ben Vagle: My thesis, which I wrote under Professor Brooks’ supervision, was on the economic costs of a conflict between the United States and China. It was a passion project of mine. I ultimately found that China would lose between 5 and 11 times more economically, from a conflict, than would the United States. These findings surprised both Professor Brooks and me, and we knew that they needed to be published.

Stephen Brooks: Ben’s findings in his thesis strongly cut against the conventional wisdom that the U.S. will be unable to economically damage China in a conflict situation without causing almost as much economic damage to itself. Because Ben’s findings were so surprising, we agreed that much more analysis of the true state of China’s economy and technological capacity was needed so that people would believe these findings. The findings were so arresting and counterintuitive that we decided it would take an entire book to show why they were, in fact, valid.

What makes the findings in the book so groundbreaking?

Vagle: We found in the book that the U.S. retains a substantial lead in economic power over China due to the large number of multinational corporations that are under its control as well as a variety of factors that overstate China’s economic capacity. And we found that, as noted, China would lose much more than would the United States in a conflict if the U.S. and its allies can act together to economically cut it off.

Why is this book particularly significant right now? Why should we be paying attention to foreign policy with respect to China?

Vagle: The rivalry between the United States and China is one of the most important issues—if not the most important issue—that the U.S. faces on the international stage. China is one of our largest trading partners; the gyrations in the stock market recently as a result of President Trump’s tariff announcements against it underscore that point. And militarily, a conflict between the United States and China over a territory like Taiwan is arguably the most important contingency that our military may face.

Brooks: The potential for war between China and the U.S. regarding Taiwan is the most dangerous flashpoint America faces. To this point, it has been assumed—incorrectly—that America lacks effective economic tools that it can use to either deter China from attacking Taiwan or to punish it afterward if it does attack. Our book shows that the U.S. does, in fact, have a hugely powerful economic tool that it can deploy against China, either on its own or in conjunction with the use of the military. If the U.S. recognizes that it has this economic tool and is wise in terms of husbanding and deploying it, then we assess that the chances of a U.S.–Taiwan war can be reduced.

You initially note that the conventional view in Washington is that Chinese economic power is nearing that of the U.S. How did this become the perception in the first place?

Brooks: Many analysts incorrectly express gross domestic product (GDP) in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms to compare the economic size of the U.S. to that of China. But this is a measure that was designed for, and should only be employed for, making comparisons of consumer welfare, not geopolitical power. To measure geopolitical power, analysts must use nominal GDP, which indicates that China is not economically larger than America, but is instead around two-thirds of America’s size. And even this nominal GDP measure is overstated because it takes China’s GDP figures at face value, which is not appropriate because China’s true GDP figures are lower than what they are measured to be for a variety of reasons. Taking account of these distortions, our estimate is that China’s current GDP is slightly less than half the GDP of America.

You argue that, instead, U.S. economic power still greatly surpasses that of China. What evidence do you cite to support this?

Vagle: Many of the conventional measures of economic power, like GDP, don’t take globalization into account. GDP aggregates all of the economic activity occurring within the territory, but it doesn’t recognize the fact that it is rare that complex goods are made in just one country anymore. Often, production occurs in global supply chains that are strung across many countries, which means it’s most important to consider who owns and operates those supply chains. The United States retains a dominant influence in that regard: We found that American firms generate 38 percent of profits globally, compared to roughly 16 percent of global profits being generated by Chinese firms.

This is massively consequential, as it means that China still has a long way to go before it can overtake the U.S. economically. Moreover, the US lead is especially pronounced in high-technology sectors, which are crucial to geopolitical and military competitiveness. American firms now garner 55 percent of world profits in high-technology sectors.

When assessing Washington’s options for negotiating with China, you stress that “China can be cut off only once.” What do you mean by this?

Brooks: It is clear that China enjoys massive economic benefits from globalization that will be costly to forgo. With a substantial economic relationship left intact, Washington can signal to Beijing that it will benefit if it refrains from attacking Taiwan, but that China would incur massive economic retaliation should it decide to challenge the territorial status quo. However, if the U.S. has already cut off China in peacetime, then it would no longer be able to do so in a crisis scenario. Put another way, if the U.S. economically cuts off China in peacetime, then it will no longer have much of any economic leverage over China in a wartime scenario.

Vagle: Also, if the U.S. decouples from China in peacetime, Washington will have a harder time enlisting the help of its allies. If the U.S. were to act without its allies and economically cut off China, its losses would be nearly as high as those of China in the short term, removing much of the leverage that it has. That strongly suggests that a peacetime decoupling, as Washington appears to be contemplating now, is unwise.

Brooks: A peacetime decoupling might even create incentives for China to attack Taiwan. If the United States initiates a large-scale peacetime cutoff and China believes it cannot effectively replicate many of the goods and technologies it stands to lose, it may sense that its window of opportunity to attack Taiwan is closing; it may decide it would be best off using force quickly while its weapons, computers, and everything else still work effectively.

In the book, you lay out ways that Washington can strengthen its position in relation to China while maintaining its critical ally relationships. What are some of these suggestions?

Vagle: We believe the government should work to form new organizations capable of conducting and analyzing the effects of economic statecraft. At present, the knowledge of economic statecraft is dispersed across six mostly siloed portions of the government: the State Department, the Commerce Department, the National Security Council, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Treasury Department. That would involve creating groups at Treasury, Commerce, and NSC focused on long-term economic security planning.

We believe that China would do well to minimize its mercantilist policies—that is, subsidies and industrial policies that are displacing industries in other countries—as these practices are alienating its trading partners and may make them more likely to cooperate with Washington against China.

Brooks: We assess that the main area of economic leverage that China has over the U.S. concerns raw materials. But the good news for the U.S. is that stockpiling is a simple, cost-effective step for greatly reducing this Chinese leverage. Raw materials do not “go bad,” and as a result the U.S. just has to pay once for a stockpile of the raw materials—such as cobalt—that it now depends on China for. Once it has a stockpile of these raw materials, it can use it any time in the future, even decades from now.

In contrast, stockpiling is not really an option that Beijing has for reducing its dependency on the firms from America and its allies since they are mostly sending dynamic products to China—that is, ones that rapidly change over time, such as semiconductors. Creating a stockpile of a dynamic product like semiconductors makes no sense because they do “go bad,” in that within a few years they would no longer be up to date and therefore not be useful in many geopolitical applications.

What do you hope readers take away from your book?

Vagle: Our book overturns many pillars of conventional wisdom with respect to U.S.–China relations, but to do so it also overturns much conventional wisdom on how to measure economic power. So, we hope readers can come away with not just a deeper appreciation of what the balance of economic power between the U.S. and China is, but also with an understanding of the tools and measures needed to evaluate this balance.

I’d like to add that Dartmouth played a massive role in enabling this project. From providing funds for conferences, to having an amazing roster of faculty who served as sounding boards for our ideas, to organizations like the Dickey Center that connected us with policymakers, Dartmouth was behind us at every step of this project.