We usually think of satellites as small objects orbiting planets or stars. But in the broader universe, galaxies themselves can have satellites—smaller galaxies bound by gravity that orbit a larger host, carrying with them stars, gas, dust, and dark matter.

Most of what we know about satellite galaxies comes from studying the Milky Way and other similarly large galaxies. But a new study led by Dartmouth astronomers broadens that understanding by exploring the satellites of dwarf galaxies—systems less than a tenth the size of the Milky Way.

The multi-institutional survey, published in The Astrophysical Journal, nearly triples the number of dwarf galaxies surveyed for satellites. The study team identifies 355 candidate satellite galaxies, including 264 that were previously undocumented. The researchers suggest that 134 of these candidates are highly likely to be satellite galaxies.

“Studying these systems can help us piece together conditions in the early universe,” says author Burçin Mutlu-Pakdil, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy.

“This project fills a critical gap, offering fresh insights into the process of how galaxies form and its connection to dark matter," Mutlu-Pakdil says. "Our goal is to build a statistical sample of the smallest galaxies in the universe, as they are the most dominated by dark matter and serve as clean laboratories for understanding its nature.”

The survey was led by Laura Hunter, a postdoctoral fellow in Mutlu-Pakdil’s research group and corresponding author of the study. In addition to Mutlu-Pakdil, co-authors of the study include Rowan Goebel-Bain ’25 and Guarini graduate student Emmanuel Durodola.

By analyzing the satellite galaxies orbiting host galaxies of various sizes and environments, the researchers aim to uncover how external conditions influence satellite formation. For instance, studies of large, Milky Way-sized galaxies suggest that larger galaxies tend to host a greater number of satellite galaxies.

“With this survey, we’ll be able to test whether those predictions hold true with much smaller host galaxies,” says Hunter. “Astronomy is a field where you can’t run experiments; all you can do is observe and make as many measurements as you can, and then put that data into a simulation and see whether it reproduces your observations. If it doesn’t, that tells us that there’s something wrong with our assumptions or our model of the universe.”

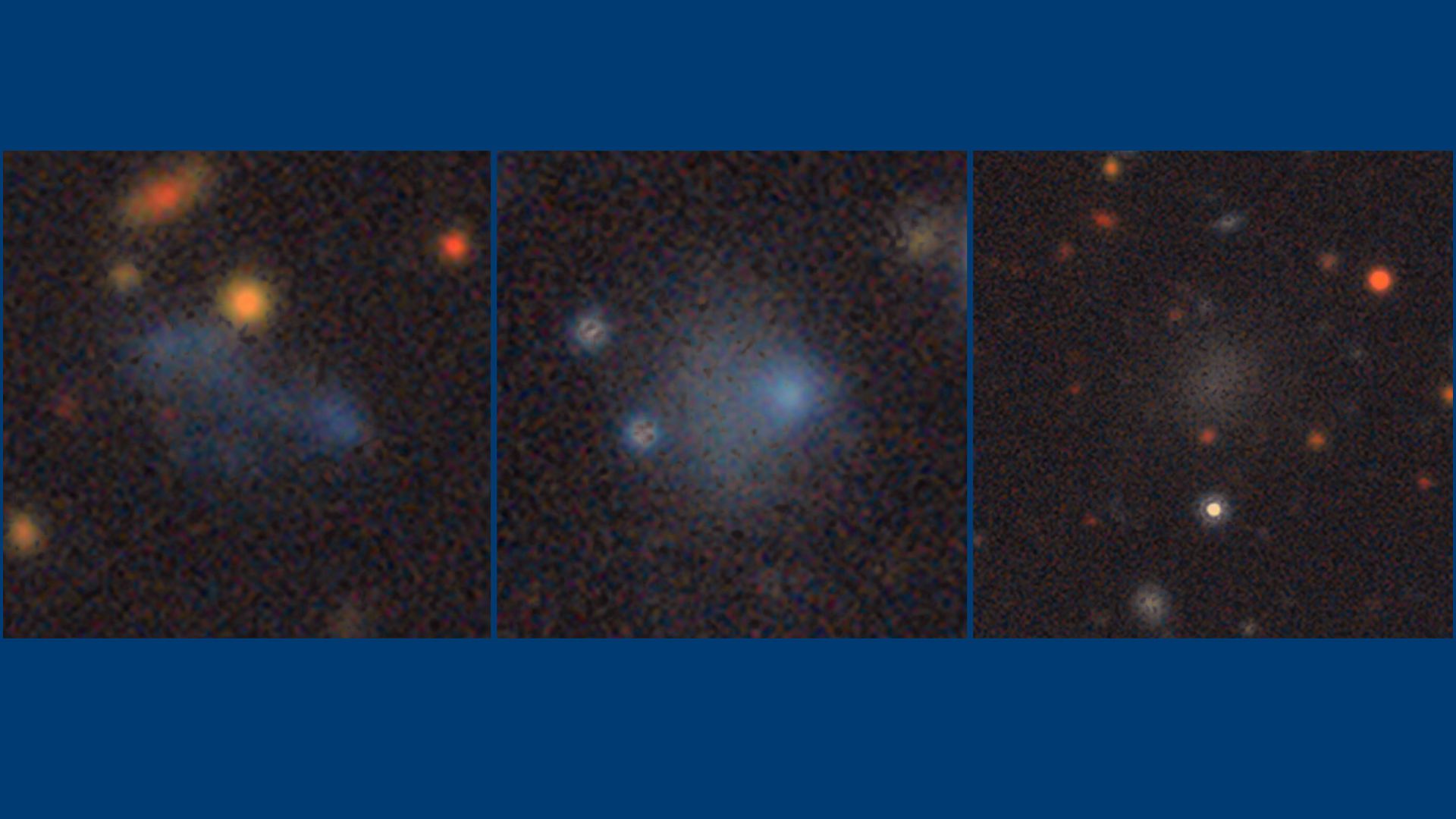

Candidate satellite galaxies for a dwarf galaxy called ESO486-G21 (Photos by Laura Hunter)

To search for dwarf satellites, the team analyzed publicly available imaging data from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) Legacy Imaging Surveys. They selected 36 host galaxies to investigate, which varied in size and in their proximity to other galaxies, since these factors could impact satellite formation. The researchers used an algorithm to remove “noise” from the images, such as bright sources of light from other stars or galaxies, and to identify objects that could be satellite galaxies. Then, they visually inspected each candidate satellite to rule out those that were due to image defects or faint light halos around bright stars or galaxies.

This survey is the first step towards understanding how dwarf satellites differ from the satellite galaxies of larger hosts. The team is currently conducting a follow-up campaign to confirm that the candidate satellites are indeed satellite galaxies, and to characterize properties such as their size, distribution, how much gas and debris they contain, and their rates of star formation.

“Getting the answers will require a lot of resources and telescope time, but the impact will be incredible for understanding the nature of dark matter and galaxy formation at the smallest scale,” says Mutlu-Pakdil. “Each one of them holds a little clue about the physics of how galaxies form.”