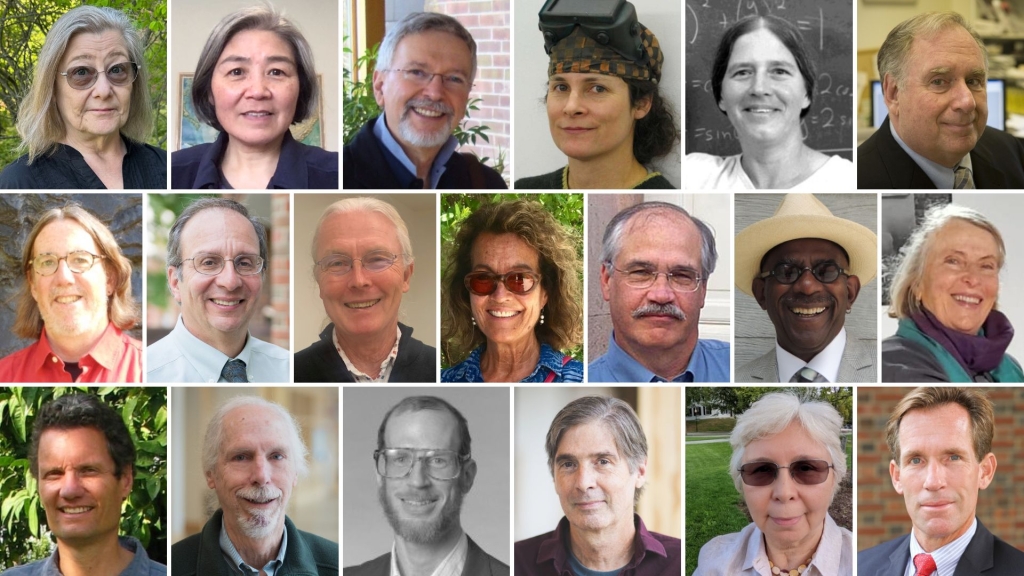

Nineteen long-serving faculty members in Arts and Sciences will retire from Dartmouth this year, each having contributed profoundly to the institution’s academic life.

“Our retiring faculty in the Arts and Sciences have made extraordinary contributions—to their fields, to Dartmouth, and most of all to generations of students,” says Elizabeth F. Smith, dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. “The collaborations they fostered and the intellectual communities they helped shape will continue to have an impact for years to come.”

Several faculty shared reflections about their time at Dartmouth and future plans. The retiring faculty members are:

- Sharon Bickel, professor of biological sciences

- Xiahong Feng, Frederick Hall Professor of Mineralogy and Geology

- Rodolfo Franconi, associate professor of Portuguese and Spanish

- Brenda Garand, professor of studio art (who retired in October, 2024)

- Marcia Groszek, professor of mathematics

- Alan Gustman, Loren M. Berry Professor of Economics

- Frank Magilligan, Frank J. Reagan '09 Chair of Policy Studies

- Michael Mastanduno, Nelson A. Rockefeller Professor of Government

- C. Robertson McClung, Patricia F. and William B. Hale 1944 Professor in the Arts and Sciences

- Beatriz Pastor, professor of Spanish and comparative literature

- Kevin Reinhart, associate professor of religion

- Silvia Spitta, Robert E. Maxwell 1923 Professor of Arts and Sciences

- Roger Ulrich, Ralph Butterfield Professor of Classical Studies

- Ross Virginia, Myers Family Professor of Environmental Science

- David Webb, professor of mathematics

As well as teaching faculty:

- John Lee, senior lecturer of studio art

- Alfia Rakova, research assistant professor of East European, Eurasian, and Russian studies

- Hafiz Shabazz, adjunct assistant professor of music

- Ronald Shaiko, senior fellow at the Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for Public Policy and the Social Sciences

Sharon Bickel

Professor of Biological Sciences

When Sharon Bickel arrived at Dartmouth in 1997, the cell biologist was drawn by the promise of a liberal arts teaching community—one where she could build a life in a beautiful place while launching a federally funded research program. More than 25 years later, that program is still going strong.

The tiny key to Bickel’s research is Drosophila—the common fruit fly—whose chromosomes segregate during meiosis, the kind of cell division that gives rise to eggs or sperm.

“In humans, chromosome segregation errors are the leading cause of miscarriages and congenital syndromes,” says Bickel. “My lab has used Drosophila to answer questions about the orchestration driving accurate segregation and how and why aging leads to increased chromosome segregation errors.”

“The inner workings of the cell are complex but so incredible,” says Bickel. “I don’t think I will ever lose the childlike wonder that I first experienced learning about cell biology.”

As a teacher and mentor, Bickel has shared that sense of awe with hundreds of students while deepening our understanding of how cells behave. She’s grateful—and a bit surprised—that her current research feels like the most exciting of her career.

In retirement, she looks forward to fewer hours in the lab and more time outdoors.

Xiahong Feng

Frederick Hall Professor of Mineralogy and Geology

Xiahong Feng is a geochemist who uses stable oxygen, hydrogen, carbon, and nitrogen isotopes to study climate and environmental changes. She joined Dartmouth’s faculty in 1994.

“The most memorable project I have done so far was in the Arctic,” she says. “We set up pan-Arctic stations to collect precipitation, rain, and snow. The goal was to assess how the melting of sea ice would result in increased ocean surface evaporation and precipitation in the Arctic, and how this process feeds back to ongoing climate change.”

The project took Feng and her team to several Arctic locations and yielded significant publications.

“We showed that sea ice reduction has resulted in an increased proportion of Arctic moisture that contributes to Arctic precipitation,” she says. Feng has also conducted field studies in North America and Asia.

In 2023, she was named a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science for her contributions to the field of geochemistry. The distinction is among the highest in the scientific community.

Currently, Feng is organizing her years of precipitation data for submission to international open-access databases.

Meanwhile, she’s enjoying two new hobbies: Chinese painting and dancing.

Rodolfo Franconi

Associate Professor of Portuguese and Spanish

Rodolfo Franconi first came to Hanover as a visiting professor in 1987, left for a few years to teach at Vanderbilt, and returned to Dartmouth in 2001—the same year he received a Distinguished Teaching Award.

“During my 34 years at Dartmouth, one of my most enduring contributions was the creation and development of the Portuguese Program,” says Franconi. “I had the privilege of designing and leading the LSA, LSA+, and FSP programs and seeing them become cornerstones of Lusophone studies on our campus.”

Initially focused on Portuguese literature, Franconi shifted his scholarly focus to Brazilian literary and cultural production, especially literature written during military dictatorships in Latin America. He also developed a comparative framework he calls the “oblique gaze,” by which neighboring societies, especially in Portuguese- and Spanish-speaking worlds, “see each other not directly, but at an angle, filtered through stereotypes, historical asymmetries, or cultural misunderstandings. It’s a way to study how we look—and often fail to look—at the other.”

In the classroom, Franconi says he strove “to blend literature, history, and film so that students could see Latin America not as a fixed geography, but as a dynamic and contested cultural space.”

Retirement will give him more time to work on a project close to his heart: the study of his paternal grandmother’s wartime diaries.

Marcia Groszek

Professor of Mathematics

Marcia Groszek, a specialist in mathematical logic, joined Dartmouth’s Department of Mathematics in 1984.

“Like most mathematicians, we logicians spend much of our time pursuing technical mathematical questions,” she says. “But the roots and motivating questions of our field concern the very nature of mathematical truth, knowledge, and proof.”

Her work builds bridges between set theory, which provides a foundation and language for mathematics; recursion theory, the abstract study of computable or algorithmic procedures and definitions; and reverse mathematics, which analyzes the logical strength of mathematical theorems.

Among Groszek’s favorite teaching projects is developing and teaching interdisciplinary courses—such as one on the mathematics and philosophy of infinity. She has also played an active role in preparing graduate students to teach and supporting their professional development.

In an interview featured in Women in Mathematics: The Addition of Difference, Groszek credits the Hampshire College Summer Mathematics Program, which she attended in high school, with giving her the confidence to pursue a field that was then largely dominated by men.

“It put me in a situation where I wasn't automatically a complete oddball for being interested in math,” she said.

Alan Gustman

Loren M. Berry Professor of Economics

Alan Gustman enters retirement with a well-researched understanding of what lies ahead—at least in economic terms.

“Together with colleagues Thomas Steinmeier and Nahid Tabatabai, I’ve built econometric models to explain the many dimensions of retirement and the wide variation in individual retirement behavior,” he says.

Over decades, Gustman has investigated how pensions and Social Security shape retirement decisions and saving behavior. His research has examined retirement incentives in pension plans, disparities in financial knowledge and saving among those nearing retirement, and the public policy questions that arise from those findings.

That work has been grounded not only in theory but in national service. Gustman served as special assistant for economic affairs at the Department of Labor, spent 47 years as a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research, and held key roles on the Executive Committee of the Retirement Research Center at the University of Michigan. His research was supported by millions of dollars in grants from organizations including the National Institute on Aging and Social Security Administration. This year, he will be honored with the Dean of Faculty Award for Exceptional Service.

Yet for all his accomplishments in service and research, Gustman takes equal pride in his teaching. Over 56 years at Dartmouth, he taught some 6,000 students to think critically about economics and public policy.

“Some of them have been spectacular,” he says, citing Stanford professor David Kreps ’72, who was named the best economist in the U.S. under age 40.

He also treasures the academic community that shaped his career. “The greatest pleasure of my career came from having wonderful colleagues—outstanding scholars devoted to fostering the highest quality teaching and research in economics.”

Frank Magilligan

Frank J. Reagan '09 Chair of Policy Studies

Frank Magilligan has spent more than three decades at Dartmouth exploring how water systems shape the Earth—from analyzing the impacts of hurricanes to reconstructing climates from 20,000 years ago using ancient flood data.

Fieldwork has taken the geographer to Iceland, China, and Peru, as well as waterways closer to home. “My graduate students and I have been documenting the significant geomorphic effects of Hurricane Irene that devastated numerous watersheds in Vermont,” he says.

A Fellow of both the American Association of Geographers and the Geological Society of America, Magilligan was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship and the Dean of Faculty Award for Exceptional Service in 2020. This spring, he received the Melvin G. Marcus Distinguished Career Award from the American Association of Geographers for his outstanding research and commitment to mentorship. This year, he will be honored with Dartmouth’s Elizabeth Howland Hand-Otis Norton Pierce Award for his outstanding teaching of undergraduates.

Magilligan credits Dartmouth’s small size with fostering interdisciplinary collaboration. “I've had some of the best conversations of my life in the Fairchild parking lot, running into colleagues from physics, astronomy, Earth sciences, and environmental studies,” he says. “Sometimes those conversations lead to great professional adventures.”

In retirement, he looks forward to finishing the book he began during his Guggenheim fellowship—an exploration of the science and politics of river restoration across the United States.

Michael Mastanduno

Nelson A. Rockefeller Professor of Government

Since joining Dartmouth in 1987, Michael Mastanduno has built a distinguished career exploring the intersection of economics and politics in international relations.

“How do global political developments shape the world economy, both historically and today? What impact do economics and technology have on the international political order? In books, articles, and seminars, I explore these questions—especially the evolving role of the United States,” he says.

His course Economic Statecraft in International Relations has produced numerous publications by undergraduate students. “Teaching Dartmouth undergraduates has been the ultimate career privilege—and what I’ll miss most,” he says.

Mastanduno received the Karen E. Wetterhahn Memorial Award for Distinguished Creative or Scholarly Achievement in 1992 and a Distinguished Teaching Award the following year. This year, he will be honored with the Robert A. Fish 1918 Memorial Prize to commemorate a career of contributions to undergraduate teaching at Dartmouth. Over the decades, he’s participated in a Washington, D.C. seminar with U.S. government officials, bringing international relations scholarship into conversation with foreign policy. He also co-authored the widely used textbook Introduction to International Relations and hosted The Briefing, a world affairs show on Sirius XM Radio.

During a sabbatical, Mastanduno served as a U.S. trade negotiator. He’s held visiting professorships in London, Milan, and Tokyo, and served in leadership roles as director of the Dickey Center for International Understanding and dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

In retirement, he plans to keep writing on global issues and traveling internationally.

“Whatever the adventure,” he says, “I’ve always returned to my enduring passion: working with generations of students—and with colleagues—on the timeless questions of international relations.”

C. Robertson McClung

Patricia F. and William B. Hale 1944 Professor in the Arts and Sciences

C. Robertson McClung, who joined the faculty in 1988, is internationally recognized for his pioneering research on plant circadian rhythms. His work has illuminated how these internal clocks function in plants and influence key processes like photosynthesis and stress response—research that has gained new relevance as climate change pushes domesticated crops into unfamiliar environments.

Beyond the lab, McClung has built a lasting legacy of service and mentorship. He has trained more than 100 undergraduates—19 of whom completed honors theses—along with 12 graduate students and 16 postdocs. “Any success I can claim needs to be shared among the full roster of my lab over the years,” he says. “Lately, I’ve noticed that the mentoring has become reciprocal—our recent forays into genomics rely absolutely on the intelligence and fearlessness of my most recent postdocs.”

McClung has also held several key leadership roles at Dartmouth, including associate dean for the sciences, chair of the Department of Biological Sciences, and one of the earliest chairs of the Molecular and Cellular Biology graduate program. “I am deeply gratified that the program has grown and continues to thrive more than a quarter century later,” he says.

Nationally, he served as president of the American Society of Plant Biologists and as a member of the National Science Foundation’s Biological Sciences Advisory Committee.

This fall and winter, McClung and his wife, Professor of Biological Sciences Mary Lou Guerinot, will spend time at the Salk Institute in San Diego, where Guerinot is a non-resident fellow and McClung will study plant genomics in the lab of his former graduate student, Todd Michael, Guarini PhD ’02.

Kevin Reinhart

Associate Professor of Religion

Since arriving at Dartmouth in 1983, Kevin Reinhart has immersed himself in Islamic intellectual history, with a focus on legal theory, theology, ritual, and Ottoman traditions. He’s studied and lived for long periods of time in many Middle Eastern countries, including Egypt, Turkey, Yemen, and Morocco.

Reinhart is the author of Before Revelation: The Boundaries of Muslim Moral Knowledge. His 2020 book, Lived Islam, explores Islamic practices in different locales.

Throughout his academic career, Reinhart says he’s posed two basic questions: “Why do the people I study all call a certain set of activities, however much they may differ from those of other Muslims, ‘Islam’? And why do I myself call those activities ‘Islam’?

Looking back at his Dartmouth career, Reinhart says he has most enjoyed engaging with students. “Some were brilliant. Just as rewarding was working with curious, bright students who—even if they were going on to some quite different field of work—understood that curiosity can bring real gratification when it leads to the labor of understanding something new. “

Much of this learning, Reinhart recalls, happened off campus, during field study programs he led to Morocco and Scotland. “The best students tried to learn as much as possible about the place and the people—through reading, talking to people, participating in institutional activities, and attention to the coursework, and through attentive travel—with the group and on their own,” he recalls.

About his next chapter, Reinhart says, “Scholars can keep on being scholars after they retire. I’ll return to a survey of Islamic ritual, which incorporates ideas about the study of ritual in general. That's how I plan to spend my time, in addition to traveling in the Islamic world and elsewhere.”

Ross Virginia

Myers Family Professor of Environmental Science

An ecosystem ecologist who studies soil nutrient cycling and plant responses to climate change, Ross Virginia arrived at Dartmouth in 1992 to chair the Environmental Studies Program.

“Coming from a large biology department and ecology group at San Diego State, my learning curve was steep, but I was taken by the challenge to envision how a liberal curriculum could approach learning and research about human relationships with the environment by integrating the sciences, social sciences, and humanities to solve real-world problems,” he says. “I am proud to have been part of building a legacy that sets Dartmouth at the top of this field.”

During the second half of his career, Virginia focused on Arctic policy and global environmental issues as director of Dartmouth's Institute of Arctic Studies in the Dickey Center for International Understanding and as co-director of the University of the Arctic Institute for Arctic Policy. He’s taken part in more than 20 field expeditions into the polar deserts of Antarctica.

“In the tundra of Greenland, I seek to understand how the thawing of permafrost in response to climate warming affects the release of greenhouse gases, furthering more warming,” says Virginia. “As we approach tipping points in climate and biodiversity, team research, which Dartmouth supports, is our best hope.”

Accepting an invitation from the State Department during the Obama administration, Virginia co-developed and led the Fulbright Arctic Initiative. “I am honored to have Virginia Valley named in recognition of my research in the Dry Valleys of Antarctica,” he says. “I smile thinking about this remote and beautiful mountain valley where I have so many memories of working alongside talented, dedicated Dartmouth colleagues and students.”

Looking ahead, Virginia plans to spend time at Rauner Research Library digging into archives about Dartmouth’s famed explorer, Vilhjalmur Stefansson, and his relationships with Greenland spanning the early 20th century through the Cold War.

David Webb

Professor of Mathematics

In 1966, the Polish-American mathematician Marc Kac posed the question: Can you hear the shape of a drum?

“The idea behind this, although it was phrased in acoustic terms, was to try to get a handle on some of the mathematics underlying quantum mechanics,” says David Webb. “If you had perfect pitch and you could hear all the overtones of the sound of hitting a drum with perfect precision, could you recover the geometric shape of the drum head?”

Together with Carolyn Gordon and Scott Wolpert, Webb famously published examples of distinct plane “drums” which “sound” the same.

Webb specializes in algebraic K theory, which he describes as “an obtuse and technical area that has ramifications in a number of other areas, including geometry, topology, and operator theory.”

Over the course of 35 years of teaching, he says he has appreciated the “talent, versatility, creativity, and initiative exhibited by Dartmouth students,” some of whom had excelled at math in high school, and others who arrived as novices in the field.

“There was a student whom I taught a few years ago in an introductory course during the pandemic,” he recalls. “He had come from a small town in Mississippi, without any mathematical background.” After taking a remedial math course, Webb’s student “went like gangbusters through the program” and is now pursuing a PhD at Cornell.

Even as he leaves teaching, Webb plans to continue learning. “There are aspects of physics that I would like to understand a lot better,” he says.

John Lee

Senior Lecturer in the Department of Studio Art

John Kemp Lee first arrived on the Dartmouth campus as a freshman in 1974, intending to study medicine. “But as a senior, I took a sculpture class with Professor Boghosian,” says Lee, “and that changed everything.”

Lee went on to pursue a career in sculpture, earning his BFA from the Maine College of Art and his MFA from the University of Pennsylvania. His work has been widely exhibited in the United States and globally, including at the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the National Academy.

Lee joined the faculty in 1984, teaching classes in sculpture, drawing, and printmaking, as well as senior seminars.

“The ability, and desire, to create is among those important things that make us human,” Lee says. “Sculpture is a language unto itself, and it allows for deeply rooted communication between individuals who do not speak, or write, in a common language. As the poet Mary Oliver wrote in her poem Instructions for Living a Life: ‘Pay attention; be astonished; tell about it.’ Sculpture, for me, has always been my way of telling about it.”

Lee says the highlights of his career have been the relationships that he’s made through the shared experience of making art, as well as hearing from former students who, at mid-career, tell him they “understand what it was that we were really trying to do back in the old Roger's Garage Sculpture Studio. That is very gratifying.”

In his retirement, Lee plans to continue making art—but now, more than ever, his focus will be creating pieces for and about “people that I love.”

Alfia Rakova

Research Assistant Professor in the Department of East European, Eurasian, and Russian Studies and Director of the Language Program

Alfia Rakova joined Dartmouth in 2007 after eight years teaching Russian at Harvard, drawn by the chance to teach across all levels in a smaller college setting. Dartmouth offered not only that, but also the opportunity to expand the Russian language program and grow its enrollment.

“I taught five courses a year during my 18 years at Dartmouth, so a lot of students successfully completed majors and certificates in Russian,” says Rakova, who holds a PhD from Kazan University.

In her teaching and research, Rakova focused on Russian morphology—the principles that guide word formation—and the specifics of learning foreign languages, including the cultural aspects. She infused her courses with exposure to Russian culture, from films and music to contemporary books and food.

For example, she took her students to a Russian restaurant in Boston, where “they sampled Russian foods and conversed in Russian,” and visited a Russian food store and bookstore and chatted with Russian-speaking locals. “Language learning is a nonstop process, and I was happy to give our students this opportunity to educate themselves and enjoy learning.”

Rakova says her students have helped her understand that learning a foreign language requires making constant choices: grammatical, lexical, stylistic, and so on. “This awareness, in turn, has led me to understand the importance of intention in every speech act,” she says. As an instructor, she helps students “express their thoughts, feelings, and values in accordance with their intentions.”

Rakova was recognized with the 2011 Dean of the Faculty Teaching Award for her outstanding contributions to Dartmouth and career distinction.

She has many plans for her retirement, including “to learn Italian!”

Hafiz Shabazz

Adjunct Assistant Professor

For over four decades, master drummer and ethnomusicologist Hafiz Shabazz has brought global musical traditions to life at Dartmouth—inviting students into a powerful conversation across cultures, histories, and sound.

Shabazz studied drumming and folklore in Ghana, Brazil, and Cuba and has performed around the world with legends like Max Roach and Lionel Hampton. At Dartmouth, he designed and taught the Oral Tradition Musicianship class—challenging students to listen deeply and engage with music as a cultural force. Using sticks and their hands, students in the class learn how to strike a drum, the connection between drumming and a country’s culture, and the emotions that can flow through music.

“If you’re not enjoying your learning, then you’re not really learning,” he says.

Shabazz also served as the longtime director of the World Music Percussion Ensemble at the Hopkins Center for the Arts. In 2024, he received the Dean of Faculty Teaching Award in recognition of his outstanding contributions to Dartmouth and career distinction.

Ronald Shaiko

Senior Fellow in The Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for Public Policy and the Social Sciences

Ronald Shaiko joined Dartmouth’s government department in 2001. Five years later, he was named a senior fellow at the Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for Public Policy and the Social Sciences, where he also served as the associate director for curricular and research programs.

“At the outset of my time at the center, Professor Andrew Samwick and I redesigned the public policy minor,” he says. Before that transformation, 50 to 60 students enrolled in public policy classes. Within two years of the redesign, that number grew nearly tenfold.

Shaiko has taught more than 3,000 students at Dartmouth and directed or co-directed two programs that have greatly advanced the Rockefeller Center’s experiential learning mission.

“Students who take my Introduction to Public Policy class and a social science research methods course become eligible to apply for the First-Year Fellows program, spending the summer working with Dartmouth alumni mentors active in public policy in Washington, D.C. This program is now fully endowed through the generosity of more than two dozen Dartmouth alumni.”

Shaiko also led the Class of 1964 Policy Research Shop, a student-staffed, faculty-mentored research enterprise that serves the Vermont and New Hampshire state legislatures as well as statewide, regional, and local commissions in both states. Since its inception in 2005, more than 600 of his students have presented more than 250 policy briefs to policymakers in both states.

As a volunteer assistant coach for the men’s cross-country team and the faculty advisor for the men’s and women’s track and field and cross-country teams, Shaiko logged, over two decades, more than 50,000 miles on team buses and more than 10,000 miles in flights to competitions.

“Teaching and mentoring students as well as providing advice and counsel to student-athletes have been the twin joys of my time at Dartmouth,” he says.