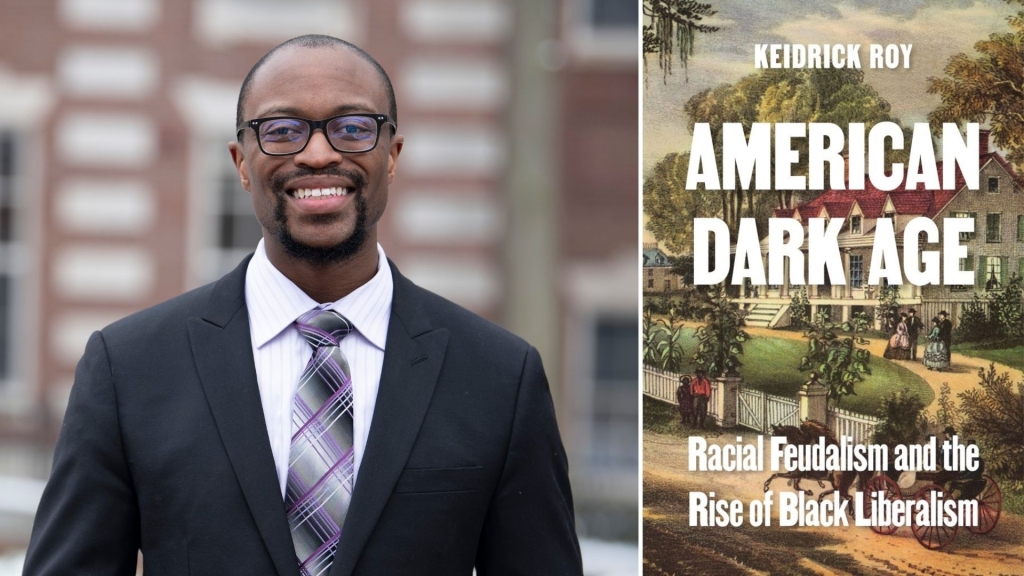

Debut scholarly books rarely earn widespread recognition—but Keidrick Roy’s American Dark Age: Racial Feudalism and the Rise of Black Liberalism has done precisely that, earning an array of accolades and critical acclaim.

The book received the 2025 Society for U.S. Intellectual History Book Prize, the 2025 Best Book in American Political Thought Award from the American Political Science Association, and three separate honors from the 2025 Phillis Wheatley Book Awards. It was also named one of the Best Black History Books of 2024 by the African American Intellectual History Society.

Roy, an assistant professor in the Department of Government, was also featured in an author-meets-critics panel at the Politics, Philosophy, and Economics Society in London and will appear in a similar session at this month’s annual meeting of the American Political Science Association.

American Dark Age uncovers a surprising intellectual paradox: while 19th-century American thinkers publicly embraced Enlightenment ideals and rejected the feudal hierarchies of Europe, they continued to use medieval metaphors to describe slavery and racial inequality. These feudalistic comparisons, Roy argues, served as ideological tools and helped justify racial stratification in the New World. For Black abolitionists, they exposed the deep contradictions between America’s liberal promises and its social realities.

In a Q&A, Roy discusses the motivations behind the use of feudalistic language in the New World—and what Enlightenment thinkers can still teach us as we confront racial feudalism in modern America.

What was the impetus for this book?

This project originated from my interest in how American writers—particularly African Americans—have engaged with European Enlightenment ideas such as reason, science, liberalism, and progress since the 1700s.

I began to wonder about the configurations of power that Enlightenment thinkers were attempting to escape. Put differently: What was the opposite of enlightenment? What did Americans most fear about the frameworks of their European forebears? I found that many were aghast at the potential return of feudalism, or what some even called the “Dark Ages.”

Jefferson, for example, regarded the period before William the Conqueror’s 1066 invasion of England as a shining example of Anglo-Saxon freedom, and he lamented the imposition of what he saw as feudal abuses during the Norman conquest. In his autobiography, he claimed to have crafted laws that eliminated the vestiges of feudalism from the state of Virginia.

And yet, despite Jefferson’s best efforts to remove the “feudal and unnatural distinctions” he so despised, he remained an enslaver. He seemed blind to how he perpetuated feudalistic notions through the enslavement and subordination of Black people.

As I examined abolitionist slave narratives, pamphlets, and speeches as well as proslavery writings from the 1800s, I found that African Americans, too, employed the language of feudalism not only to describe the abuses of medieval Europe, but also to critique Jefferson’s modern America.

Your book coins the concept of racial feudalism. How do you define it, and how did this ideology take hold in the New World?

Racial feudalism encompasses both the language and ideas that abolitionists and proslavery thinkers used—in diametrically opposite ways—to interpret what they saw as the antebellum remnants of the medieval world that persisted in modern, color-based hierarchies. African American abolitionists lamented the paternalism, notions of “mutual” obligation, and racially coded pecking orders of slavery and racial prejudice, often using terms such as “feudalism,” “vassalage,” “serfdom,” and the “Dark Ages.”

Black abolitionist James W. C. Pennington, for example, denounced slavery in 1841 as “an institution of the dark age!” and asked, with scarcely veiled sarcasm, “Did the monarchs, patriarchs, and prophets of the south ever think of this?”

Proslavery activists, by contrast, celebrated these arrangements as a perverse affirmation of their European medieval heritage. A half-century earlier, at the 1787 Constitutional Convention, slavery proponent Charles Pinckney referred to Black people as “the labourers, the peasants of the southern states.” Proslavery theorist George Fitzhugh, Pennington's contemporary, later urged readers to “look to the old Patriarchs and their slaves, to the feudal lords and their vassals, or come to the south and see our farms” as models for society.

While the founders generally rejected feudalism as an undesirable relic of the Old World in the late 1700s, attitudes toward the medieval era began to shift after the Revolutionary era. By the early 1800s, Americans’ suspicion of the “Dark Ages” gave way to nostalgia for chivalry, in part fueled by Sir Walter Scott’s enormously popular works like Ivanhoe (1819). Even Frederick Douglass took his surname from a Scott poem, underscoring the deep permeation of this medieval revival throughout American culture.

How did racial feudalism pose a threat to early America’s promise of democracy and liberalism?

In the 19th century, proslavery advocates often cloaked the anti-liberal and anti-democratic practices of slavery and racial domination behind romantic declarations about the medieval world. Such nostalgic visions provided a veneer of historical legitimacy to rigid hierarchies that were, in reality, oppressive and exploitative.

As Black abolitionist and lawyer John Mercer Langston observed shortly after Reconstruction, "the tendency of political thought in the South has always been towards aristocracy and feudal institutions—the right of the few to govern, the right being founded upon wealth, landed estates, and consequent social position and influence.”

In subsequent decades, organizations such the Ku Klux Klan cultivated nostalgia for a medieval past, particularly following the celebratory portrayal of the Klan in Thomas Dixon’s popular 1905 novel The Clansman. Dixon styled the KKK as the “Knights of the South” who, with their tall spiked caps, “made a picture such as the world had not seen since the Knights of the Middle Ages rode on their Holy Crusades.” The book’s 1915 film adaptation, The Birth of a Nation, spurred membership growth. It is estimated that by the mid-1920s, millions of Americans were Klansmen.

How did efforts to reject American feudalism seek to renew the country’s commitment to values such as individual liberty and egalitarianism?

African American liberals advanced an explicitly anti-feudal, anti-prejudice, and anti-patriarchal political philosophy. They resisted through vocal advocacy and written appeals. Black liberals such as Frederick Douglass, William Wells Brown, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, and Harriet Jacobs saw themselves as wholly American and many rejected efforts to send Black Americans away from the United States against their will—a measure supported by U.S. presidents such as Jefferson, Madison, and Lincoln in his early days. They also supported women’s rights, including the right to vote.

Though Douglass and other Black liberals witnessed the successes of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments, they also faced fierce backlash from those committed to preserving racial hierarchy. Nevertheless, an enduring feature of Black liberalism was the belief that social progress was possible in the United States and that African Americans could achieve justice. They had what political theorist Melvin Rogers, employing Douglass’s language, highlights as “‘sufficient faith in the people of the United States to believe that a black [person] can ever get justice at their hands on American soil.’”

How does racial feudalism manifest today?

The logic of racial feudalism surfaces today when extremist groups adopt medieval symbols to glorify mythical social orders. At the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, for example, some marchers carried crusader crosses and other medieval iconography to present white supremacy as part of a noble chivalric tradition, much as proslavery writers once cast the South as a modern feudal domain. Similar imagery appears in far-right manifestos that repurpose medievalist language to frame racial hierarchy as natural and honorable.

These contemporary reverberations are significant because they demonstrate how the rhetoric of racial feudalism continues to serve political ends: It mystifies the conditions of inequality through romanticized narratives that elevate particular groups. Understanding the use of racial feudalism during the antebellum era provides us with insight into how its language can still undermine liberal democratic ideals today.

The proliferation of extreme, anti-liberal ideologies in the United States with medievalist sympathies also remains troubling. Once considered fringe, ideas such as the "Dark Enlightenment" and the Neoreactionary or NRx movement, which reject democracy and embrace feudalistic governing structures, are edging toward the mainstream, as seen in recent media profiles of figures like Curtis Yarvin, whom I discuss in American Dark Age.

What lessons does this era impart for confronting racist and anti-liberal ideologies today?

While I examined racial feudalism as an American ideology born out of slavery that makes inherent social hierarchy appear natural, we might consider how similar ideas might be operating globally. Indeed, the same tyrannical strategies once used to restrict the rights and liberties of Black people might eventually be employed to curtail the freedoms of all people.

As we confront the effects of filter bubbles, political polarization, assaults on truth, and myriad threats to American institutions, we should recognize that African American thinkers have left us positive tools for renewal: a commitment to truth telling, political equality, reform over revolution (except in eradicating clear moral wrongs, like slavery), and collective moral improvement. For social change to be lasting, they argued, we must become better people by intentionally cultivating individual virtues and civic-mindedness.

What’s next for you?

I am in the process of rewriting what began as my dissertation project, which detailed how African Americans have taken up and transformed Enlightenment ideas, institutions, and sentiments since the 1700s. The Underground Enlightenment: A Story of the Black Reconstruction of American Thought will demonstrate how African American thinkers such as Caesar Sarter and Revolutionary War veteran Lemuel Haynes were deeply invested in Enlightenment ideas even as they expressed them differently from their founding-father counterparts.

Shortly after the signing of the Declaration of Independence—perhaps the emblematic document of what might be called the American Enlightenment tradition—Haynes crafted a lengthy public response that both challenged and extended Jefferson’s vision of America in ways that resonate today. Ultimately the project seeks to transform our collective understanding of reason, science, universalism, and progress through the eyes of early African Americans.